Imagine your company is a warehouse. When you started, you had one product on one shelf. Simple. But ten years later, you have acquired three smaller companies, launched two new service lines, and developed a piece of software.

Now, your warehouse is full, but the labeling is a mess. Customers walk in looking for your premium service but get confused by your budget product. This is “Brand Sprawl”.

At PicklesBucket, we believe branding isn’t just about aesthetics; it’s about engineering. Just as a supply chain needs a logical flow, your brand portfolio needs a clear structure to maximize efficiency and value. This structure is called Brand Architecture.

What is Brand Architecture?

Brand architecture is the organizational system that defines how your company’s portfolio of brands, sub-brands, products, and services relate to one another.

It answers the critical question: Does our new product need its own name and logo, or should it wear the parent company’s uniform?

Choosing the right model isn’t an artistic choice—it’s a strategic one that impacts your marketing budget, your cross-selling ability, and your company’s valuation.

The 3 Main Models of Brand Architecture

We view brand architecture as a continuum, ranging from “Mild” (one unified brand) to “Wild” (many distinct brands). Here is how the global giants structure themselves, and what you can learn from them.

1. The Master Brand (The “Branded House”)

In this model, the parent brand is the undisputed hero. Every product and service sits directly underneath the master logo, usually sharing the same color palette, typography, and naming convention.

- The Strategy: Maximum brand equity transfer. Every dollar spent marketing one product lifts the reputation of the entire group.

- The Risk: Contagion. If one sub-brand fails or has a PR crisis, the entire master brand takes a hit.

Global Examples:

- FedEx: Whether it’s FedEx Express, FedEx Ground, or FedEx Freight, the purple logo is dominant. The descriptor changes, but the brand promise (reliability) remains the same.

- Virgin: Richard Branson’s empire is the ultimate Master Brand. Virgin Atlantic, Virgin Active, and Virgin Moneyare totally different industries, but they all leverage the “Virgin” rebellious personality.

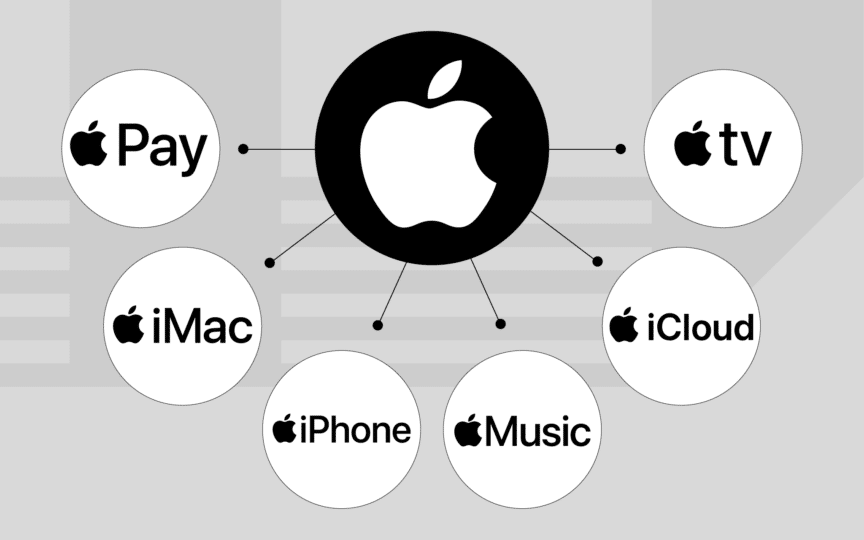

- Apple: The master of ecosystem branding. They use a “Linked Naming” strategy (Apple TV, Apple Pay, Apple Pencil, iPhone, iPad, iMac, Apple Watch). Because they are a Branded House, buying one device instantly sells you on the next one. The trust flows seamlessly across the entire portfolio. Even though the word “Apple” isn’t in the name “iPhone,” the “i” prefix is so strongly owned by Apple that it functions as a direct link to the master brand.

2. The Hybrid Model (The Spectrum of Endorsement)

This is the “Middle Ground”—and often the smartest place for industrial and B2B companies to sit. However, “Hybrid” isn’t a single setting; it is a sliding scale. Depending on how much you want to leverage the parent company’s reputation, you can choose one of four specific sub-types:

- The Strategy: It allows you to target a new niche without alienating your core customers, while still using the parent company’s reputation to close deals.

- The Nuance: As noted in modern strategy, this can be “Endorsed” (explicit connection) or “Linked” (using a shared prefix).

A. Equal Drivers (50/50 Balance) Here, the parent brand and the product brand are virtually inseparable. The consumer needs both names to understand the offer.

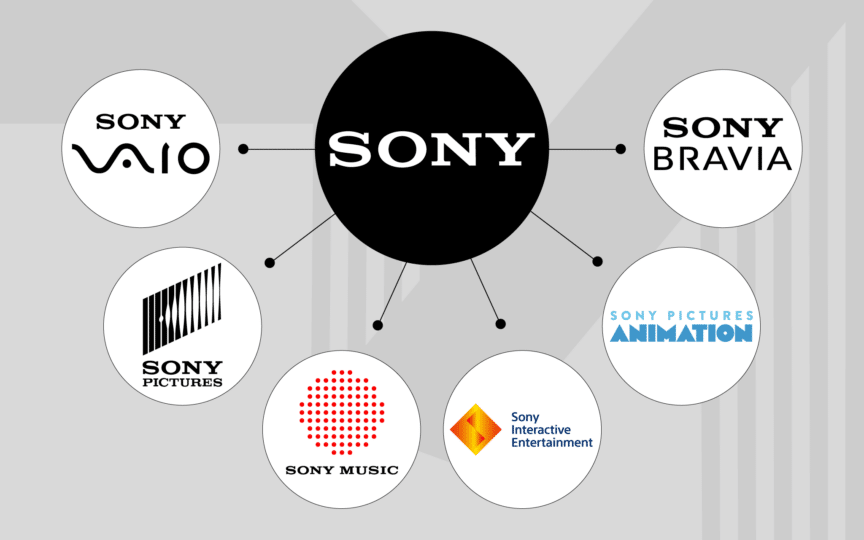

- Example: Sony PlayStation. “Sony” promises electronics quality; “PlayStation” promises gaming fun. You rarely say one without the other.

B. Strong Endorsement (“By…” Strategy) The sub-brand has a unique name and logo, but the parent brand is clearly attached as a guarantor of quality. The parent is the “safety net.”

- Example: Courtyard by Marriott. It is distinct from a luxury Marriott hotel, but the endorsement tells you the bed sheets will be clean and the service reliable.

C. Linked Naming (The Prefix Strategy) This is a subtle but powerful way to build a family without plastering the logo everywhere. You use a shared linguistic prefix or suffix to connect the portfolio.

- Example: McDonald’s. The Big Mac, McMuffin, and McFlurry. The “Mc” prefix instantly signals the brand family, even though the products look and taste completely different.

D. Token Endorsement (Product Dominant) Here, the parent brand is barely visible—often just a small “quality stamp” on the back of the package or the footer of the website. The product is the hero.

- Example: KitKat (Nestlé). You buy a KitKat because you want a break, not because you love Nestlé corporate. The parent brand is there only for legal and trade assurance.

3. The House of Brands

In this model, the parent company is invisible to the consumer. The sub-brands stand completely alone, with their own names, logos, and distinct personalities. They may even compete with each other.

- The Strategy: Maximum market share. You can sell a budget product and a luxury product simultaneously without damaging the premium brand’s reputation.

- The Risk: High cost. You cannot share marketing assets. You have to build equity for every single brand from scratch.

Global Examples:

- Procter & Gamble (P&G): You buy Pampers, Gillette, and Tide. You generally don’t care that they are owned by P&G. This allows P&G to sell different detergents to different demographics without confusion.

- General Motors (GM): A Chevrolet driver sees themselves differently than a Cadillac driver. If GM tried to sell a “$80,000 Chevy,” the market might reject it. By keeping the brands separate, GM captures both the mass market and the luxury market.

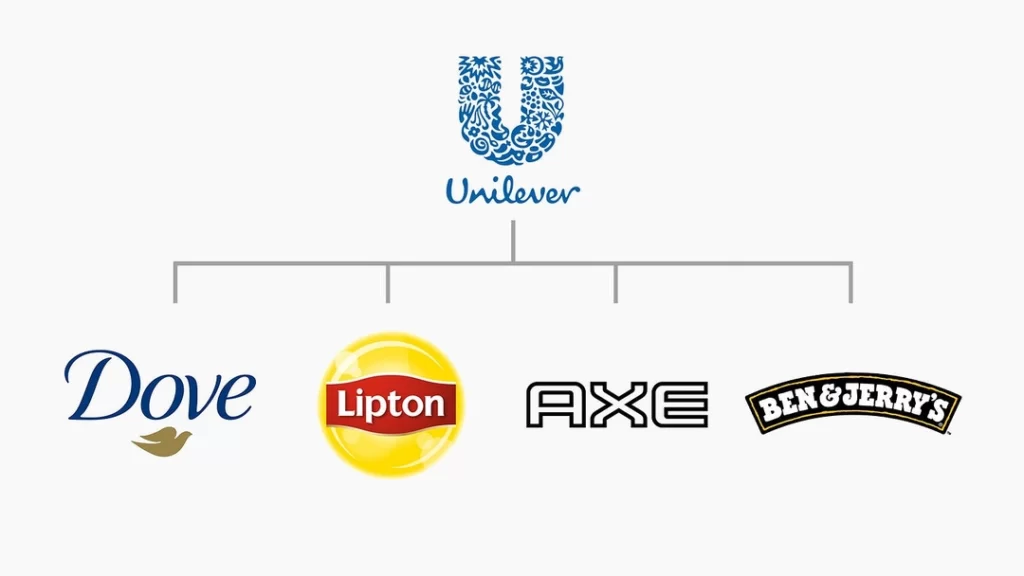

- Unilever: A classic holding company model. They own Dove (focus on real beauty) and Axe (focus on attraction). If these two brands were sold under the “Unilever” name, their messages would conflict. By keeping the parent company in the shadows (House of Brands), they can dominate opposing sides of the market.

Which Structure is Right for Your Business?

If you are an industrial firm, a tech startup, or a logistics company, you likely don’t need a P&G-style House of Brands—it’s too expensive.

However, a pure Master Brand might be too rigid if you are acquiring companies with their own legacy.

Ask yourself these three questions:

- The Audience Test: Do my different products target completely different customers? (e.g., Budget DIY vs. Premium Corporate).

- The Ego Test: Am I keeping an acquired brand name just to make the founders happy, or because it actually holds market value?

- The Budget Test: Can I afford to support two separate websites, two marketing teams, and two distinct SEO strategies?

The PicklesBucket Approach

At PicklesBucket, we don’t guess. We analyze. We treat your brand architecture like a blueprint. Before we design a logo, we look at your long-term business goals to determine if you need to consolidate, separate, or endorse your portfolio.

Is your brand portfolio growing faster than your strategy? Let’s simplify the complex.